#07: Parting Thoughts - Savarkar

#TIL moments from the life of VD Savarkar: a poet, historian, revolutionary, and the father of Hindutva ideology in India.

Dear reader,

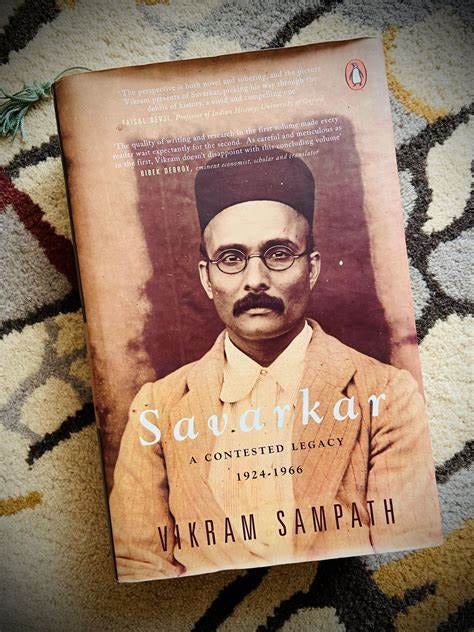

As you might be aware from some of my recent posts that I have been reading the mammoth biography of VD Savarkar by Vikram Sampath and have become somewhat obsessed by the ideas that it has spurred in me. I also have been talking to some of my friends and refining my views.

For the uninitiated, Savarkar was a revolutionary freedom fighter, sentence to the harsh sentence for life in Andaman Islands away from mainland India by the British, and who in the latter part of his life came to be identified as the father of Hindutva ideology.

After finishing up the books, I was wondering what I could communicate to you that hasn’t been communicated earlier. If you are even remotely interested in contemporary Indian politics, you might already have you mind made up on Savarkar, but to me it seems that the question is not settled and neither can it ever be. Savarkar has his moments, the good, the bad and even some that I felt were ugly.

So here is a short summary of interesting #TIL moments that I had while reading about Savarkar.

A poet, a historian and a revolutionary

Savarkar is considered to be one of the great Marathi poets and a gifted writer composing numerous poems, plays and works of literature and this earned him the adulation of many of his contemporaries.

In his youth, he gets a chance to go to England to study law and around the 50th anniversary of 1857 rebellion notices that the Britishers are setting a narrative of mutiny of a few unruly sepoys.

To counter this, he researches the facts around 1857 from the British archives and writes perhaps the first account of 1857 from Indian perspective, highlight the valour of Indians and the values that the soldiers in 1857 fought for. He renames the event as the First War of Indian Independence and his book serves as a source of inspiration for generations to come.

During his stay in London, and even before that in India, he is in close contact with many revolutionaries, known and unknown. There are elaborate plots, international conspiracies as well as real politicking that goes on to create pressure on the British.

It was fascinating to learn how all these revolutionaries, are acting like decentralised nodes of a system. However, what sets them apart from terrorists is that terrorists kill people for the sake of ideology, whereas these are ideologues who use violence as the ultimate means of expression when every other avenue is exhausted.

I still cannot condone all acts of violence, but I do have a deeper understanding of their actions which perhaps is best explained through the actions of Bhagat Singh when they fire bombs at the empty assembly benches and court arrest, not to kill people and run, but to “make a deaf system hear”.

Another interesting fact is that while Bhagat Singh is universally praised in Indian history and Savarkar eventually becomes a pariah, there is a period of time when Bhagat Singh’s “Hindustan Socialist Republican Army” requires its potential members to read Savarkar as an essential reading.

Indian Freedom fight to Hindu Hridhay Samrat

The second phase of Savarkar’s life begins after he is captured and eventually sent for double life imprisonment to Andamans. Here he is subject to intense torture just like other inmates, and starts noticing a dynamic where Britishers rely on Afghani Muslim subordinates to carry out the torture and they in turn use the power at hand to coerce and convince the inmates to convert to Islam in order to earn some respite.

Now, as per my understanding, Savarkar does not turn a stanch Hindu overnight. He has always been a proud Hindu all his life and his poetry has strong Hindu imagery, but prior to his Andamans imprisonment he doesn’t seem to exhibit any enmity towards Muslims, in fact celebrating their contribution in 1857. In Andamans, he starts convincing Hindus and other inmates belonging to “Sanatan fold” to not convert and even hosts reconversion ceremonies.

After spending years in Andamans, when he is released conditionally, he can’t go out of Ratnagiri district of Maharashtra and cannot participate in political activities. So, the only avenue left to him is reforms in Hindu society. He start working tirelessly towards eradication of Caste System, encouraging co-dining as well as educating children of different castes together. He encourages pride in Hindu identity, efforts towards which culminate in him reconversions of people back to Hinduism.

During this time, moved by the events surrounding Khilafat movement (as I have written in a previous post here) he raises an interesting question: If Muslim League claims to represent Muslim interests, and Congress stresses that it does not represent Hindu interest but interests of all Indians, who represents Hindu interests?

A few years back I would have said that since Congress was representing Indian interests which obviously includes Hindus then why do we need someone to raise Hindu interests. I have modified my position on it.

While I still believe we should be concerned with broader (Indian) interests, it is inevitable that there were be partisan interests. In such a case, introduction of a partisan interest shifts the Overton Window towards that group. However, to counter this, if we want to establish an equilibrium, my sense tells me that there needs to be a counter group to articulate the opposing views and in between these two groups, we find our truth.

To bring it back to pre-independence India, if Muslim League was demanding radical changes to accommodate Muslims, Congress could only articulate what was good for all Indian, but this would mean some Hindu interests would go unrepresented or compromised.

I don’t claim that Hindus were not represented by Congress, but more like their interests were not being negotiated by a motivated party. Congress could act like a mediator as it did, but it could not speak strongly in favour of Hindus, lest it be termed as a Hindu party, a label that it wanted to avoid all costs. In such a scheme of things, you need someone to be the voice of Hindus, to even out the odds and it seems Savarkar and the earlier avatar of Hindu Mahasabha did that.

The realist in an age of idealism

Finally the greatest and perhaps the only unblemished side of Savarkar is his brutal realism. Towards the end of 1930s and early 1940s as the world and India is pushed into a world war by the events in Europe, Savarkar’s brutal pragmatisms leads him to advocate changes and policies that seem prophetic in hindsight.

The foremost in these is the militarisation drive organised by Hindu Mahasabha under him. The idea is simple: Muslim League is enjoying greater patronage from the British by each passing day. This means that situation might arise in future where the country has to undergo a civil war. In such a case, the British Indian Army is lopsided in its composition and Muslims make 60% of the forces despite being half the number in the national population.

Thus were the British to retreat, there could be a capture of the state machinery if passions are flamed on communal lines. Secondly, since Muslims form a greater number in British Indian Army, British feel a sense of duty in advocating their interests and hence their support to the Muslim League.

Thus, to negate any future threats, Savarkar and Hindu Mahasabha organise massive drives to encourage Hindus to join the army, navy and air force. While this move might seem like strengthening British rule, it is actually a brilliant strategy and one that gets a massive boost thanks to relaxed and accelerated hiring in view of Second world war.

This seems prophetic, considering that when partition actually happens, which was not a surety when Savarkar begins, the demographics of army play a crucial role. This step is taken further by the Government of Independent India when it aims for a greater demographic diversity in armed forces. In Pakistan, where no such steps were taken, suffered a split on regional lines even after getting a religiously homogenised state and the for what remains of Pakistan, military hegemony is the greatest bane.

A sad conclusion

In my opinion, Savarkar's story doesn't have a great conclusion. Some of it is his doing, while others can be attributed to his political adversaries. Although he was implicated in the assassination of Gandhi without any proof of active involvement, his actions during the trial were cryptic, which makes it hard for me to support him.

Further, while he repeatedly mentions that post-independence “there is no longer need for any armed actions” and that all battles must be fought politically, he sometimes makes bizarre political choices and comments, some of which have inspired followers today who I doubt he would find common ground with.

He refers to Nepal’s king as a Hindu ruler, and at other time laments that that Hindu women were sacrificed because Hindu rulers did not rape and murder Muslim women like Muslim rulers did. Vikram Sampath has tried to rationalise it as a reflection of past with nothing meant for future, however I am not convinced.

It is contradictory to praise Shivaji Maharaj as an icon of pluralism and secularism in Hinduism while condemning him for not committing rapes and murders of Muslim women captured during his campaigns.

Because of all of these actions and writings, it is difficult for me as an Indian, born decades after his death, to appreciate any circumstances that might render the picture more nuanced. There is no nuance here.

But it will be unfair of me to pile all of it on Savarkar. While his actions towards the end do give the story a bittersweet twist, his political opponents highlight only his failing and ignore his massive contributions to the Indian nation, often at immense personal cost.

No wonder people now support everything unabashedly, given that everything good was buried as well. He is considered a victim today because he and his legacy were unfairly blemished by both the British and the Independent India’s Government.

Conclusion

As I had mentioned in my previous post that was inspired by his biography, a lot of what I have learnt here is new and while the shift in my views is recent I do understand that the reality can be further nuanced, hence I’m open to changing my views further, in either direction.

But beyond that, reading about Savarkar’s life, makes me realise the amount of suffering that Indians born in British ruled India undertook to free us. Further, the amount of knowledge generated as well as actions that there leaders and revolutionaries took with the limited tools that were available to them a century before me makes one realise how little we are doing with what we have.

I believe that I have a lot to offer to my country and to the world, yet there’s little action that I have taken. Sure I try to read as much as I can, and try to talk and spread ideas, but in terms of tangible accomplishments, I have little to show.

India that Savarkar was born in was poor and subjugated, while the one I’m living in is significantly richer in comparison, is the largest country in the world and a dominant power in the world. I also have better tools and resources at my disposal than Savarkar or Bhagat Singh or even Gandhi at my age, and yet I don’t think I have made any effect on the world.

I was reading a personal finance piece today, in which the author mentioned that when people talk about what being rich means, they have a number in mind but they don’t imagine what being rich will mean, but being rich is more of a state of mind than a number of a screen.

Similarly, when we think about changing our country for the better, often we think about the power (either political or in terms of reach) but what does making change really mean, if you were to actually get the power you think you need? And if we have a vision of what that impact means, what can we do today with whatever power that we have today?

Savarkar and others inspired millions and freed the subjugated country that they were born in, what can we do to further our dreams in a free India?